When most people are heading to safety, convenience stores usually stay open as long as they can without risking their employees' safety. They aim to keep the business running as long as possible and be the first to reopen when it's safe. This means making sure they have power and supplies, like fuel, food, and other essentials, and can reopen for emergency workers and customers.

Even when power is restored, there are still other issues to address, like getting fuel shipments. During peak demand, a typical retailer might sell about 1,000 gallons of fuel per hour. So, even if a store has power and the distribution system is running smoothly, they might only have a few hours to get a new fuel shipment to stay open. Depending on the location, the next fuel shipment could be hundreds of miles away because the U.S. has a regional imbalance between where fuel is produced and where it's most needed.

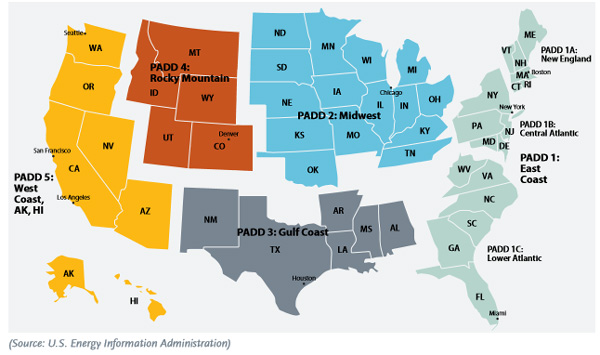

U.S. fuel distribution is defined by five Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs).

PADD 1 represents 17 East Coast states from Maine to Florida and has the largest fuel demand in the country. PADD 3, which represents six largely Gulf Coast states from Alabama to New Mexico, has the largest supply of fuel in the country. If a hurricane hits the East Coast or Gulf Coast, most fuel retailers are affected.

PADD 1 states consume more than half of the gasoline in the country, but PADD 1 refineries supply less than 10% of the gasoline refined in the country. Meanwhile, PADD 3 produces has more than 50% of the country’s refining capacity and exports approximately two-thirds of its finished product to PADD 1.

When a major storm hits the Gulf Coast, in addition to potentially disrupting crude oil production, import delivery and refinery operations, it can take pipelines offline for a period of time. Without refinery production keeping supplies steady, pipelines must slow deliveries and oftentimes create temporary shortages at terminals along their delivery route.

Even when there’s not a major storm at play, the Gulf Coast and East Coast are highly dependent on each other to balance supply and consumption of transportation fuels. The Transportation Energy Institute’s report, “Assessment of the U.S. Fuel Distribution System,” provides a broad overview of how fuel moves throughout the country.

Pipeline infrastructure linking PADD 1 and PADD 3 plays a key role in balancing supply and the use of transportation fuels within each geographic region.

Moving product from the Gulf Coast throughout the East Coast relies on the Colonial Pipeline, which transports more than 100 million gallons of product every day from 30 refineries to markets across the Southeast and Eastern Seaboard. When a major storm hits the Gulf Coast and/or the East Coast, the entire process can be disrupted.

Fuel supply outages, or even the threat of them, can lead to changes in wholesale fuel prices that quickly show up at local gas stations.

When disruptions happen, fuel retailers face changes in product availability and volatile wholesale prices. During these times, suppliers frequently update retailers about changes in wholesale prices and fuel supply limitations in their regions. Retailers selling branded fuel might see price increases and limited access to fuel. Those selling unbranded fuel, however, often face the most significant price hikes and could be denied fuel because refiners prioritize their contractual obligations. In both cases, retail prices respond accordingly.